Researchers engaged in ongoing battle to defeat mutant KRAS

Sotorasib and adagrasib, the first agents to directly target KRAS mutated- (mKRAS) cancers, became overnight sensations when they were approved in 2021 and 2022, respectively. But the race to stop mKRAS tumors is anything but a sprint. It began with the discovery of RAS in 1964, and the endgame remains elusive.

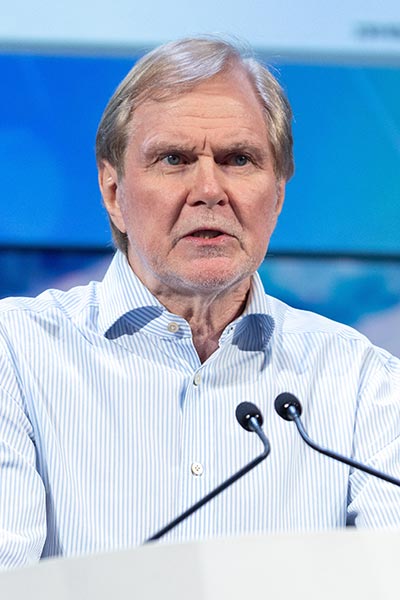

“The first serious attempt to target KRAS came in 1984 and the race began to heat up in 1992 and 1993,” said Frank McCormick, PhD, Professor of Medicine at the Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of California, San Francisco, and leader of the National Cancer Institute RAS Initiative at Frederick National Laboratory. “By 2003, there were multiple clinical trials testing farnesyl transferases. All of these trials failed.”

The problem, McCormick explained, was that farnesyl transferase inhibitors act only on HRAS, which makes up a minority of human tumors compared with KRAS mutations. Because HRAS was discovered before KRAS or NRAS, much of the preclinical studies had been conducted with the more familiar HRAS.

It took another decade to target the G12C allele to trap KRAS in its inactive GDP-bound state, and even longer to develop a covalent approach to attack both the active GTP state and the inactive GDP state.

“We will be in the clinic in late 2023 with an agent that rapidly inhibits KRASG12C binding to RAF,” said McCormick, the first speaker at the Beating KRAS: A 30-Year Overnight Sensation plenary session on Saturday, April 15. The session can be viewed on the virtual meeting platform by registered Annual Meeting participants through July 19, 2023.

“RAS mutations are found in a wide variety of human cancers,” explained Pasi A. Jänne, MD, PhD, Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Director of the Lower Center for Thoracic Oncology, the Belfer Center for Applied Cancer Science, and the Chen-Huan Center for EGFR Mutant Cancers at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “And KRAS mutations are predominant. We need multiple strategies to target multiple KRAS pathways.”

Early approaches targeted pathways upstream and downstream of KRAS. With the approval of the KRAS OFF G12C-specific inhibitors sotorasib and adagrasib, researchers are focusing on a variety of RAS ON inhibitors, as well as G12D-specific inhibitors.

There is also significant work examining the effects of sotorasib and adagrasib on the central nervous system. Up to 40 percent of KRASG12C-mutant lung cancers have brain metastases at diagnosis.

And there’s also interest in sotorasib and adagrasib in pancreatic and other gastrointestinal cancers. Multiple studies are exploring KRASG12C-inhibitor combinations and combinations with other anti-cancer agents, including immunotherapeutics.

One of the complicating factors is the multiplicity of RAS effector pathways. Many of these pathways feature mKRAS-dependent modulation of the immune environment to inhibit host anti-tumor activity, said Dafna Bar-Sagi, PhD, Saul J. Farber Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Pharmacology, Executive Vice President and Vice Dean for Science at NYU Langone Health.

“The host operates at multiple levels,” she explained. “There are tumor-host interactions at the microsystem level, the tumor microenvironment, the mesosystem, the organ environment, and the macrosystem, the overall organismal environment. There is important host-mediated reprogramming of the immune environment at each of these levels.”

Tumor cells can reprogram the immune phenotype to make the tumor microenvironment more welcoming to tumor progression. In pancreatic cancer, mKRAS tumors can induce immune suppression by upregulating production of IL-1β in the pancreatic microbiome.

At the mesosystem level, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) selectively metastasizes to the lung and liver. In the lung, metastatic PDAC upregulates the SLC6a4 serotonin transporter gene, which supports growth of lung metastases.

At the macrosystem level, increased physical activity can increase circulation of immune cells and reduce inflammation. Elevated levels of physical activity upregulate epinephrine, which recruits CD8-positive T cell from the periphery to the circulation, where they are expanded and activated by IL-15 to boost anti-tumor immunity, Bar-Sagi explained.

“We need to understand the host-tumor interaction and how it drives the immune landscape,” she said. “Identifying local and systemic nodes of immune modulation could be a necessity to improve therapeutic success.”

Leveraging mKRAS as a target for immunotherapies is another approach to improving therapeutic outcomes. Mutated KRAS elicits T-cell immunity, a target that was first explored in the 1990s with therapeutic vaccines.

“The early vaccines had minimal clinical activity,” said Beatriz M. Carreno, PhD, Associate Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. “They generated mostly CD4 response, which is not dramatically effective against mKRAS.”

More recent approaches, including adoptive transfer of mKRAS-specific tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, show more promise, Carreno said. Her lab developed a pipeline to identify and validate mKRAS epitopes and engineer a dendritic cell vaccine targeting mKRAS neoantigens.

A small proof-of-concept trial showed no serious adverse events and a 63 percent immunologic response rate with 60 percent of subjects alive with no evidence of disease at 52 weeks. A second proof-of-concept trial using neoantigen T-cell receptor (TCR) gene therapy in pancreatic cancer showed partial response at six months and long-term persistence of TCR-engineered T cells.

The next step is engineering T-cell engaging bispecific formats. One example is diabodies, in which an anti-CD3 portion is linked to antibodies that recognize the peptide-MHC complexes. Hapten-mediated antibodies have shown high specificity and robust response in preclinical work.

“KRAS is highly personal,” Carreno said. “We can target about 24 percent of G12 mutations with our current platforms. This is very precise medicine, so we need very precise and cost-effective screening mechanisms. We are poised to enter the clinic later this year.”

More from the AACR Annual Meeting 2025

View a photo gallery of scenes from Chicago, continue the conversation on social media using the hashtag #AACR25, and read more coverage in AACR Annual Meeting News.